This post has been modified 5/April/23 after discussion on twitter with @AR_Clark convinced me that the reason for the continuing decline in efficiency in warm weather is due to increasing use of the immersion heater for hot water heating. This is hopefully less common now, as heat pumps can provide all the hot water necessary except for sterilisation cycles, and sometimes even then.

We know that air source heat pumps (ASHP) are less efficient in cold weather. However this chart shows decreasing efficiency in warm weather too. The chart comes from an article recently published in Energy and Buildings [1]. It was generated using field data from UK heat pumps installed in 2012. These are quite old installations and performance has improved quite a bit since then. However, this data is still being used to predict national electricity demand in the future. In the chart each dot represents the average COP (efficiency) of all the ASHPs included in the analysis over one day. Efficiency is low in cold weather, and increases rapidly but only up to about 8°C. After that things go downhill rapidly. This is less critical than it looks as the heat demand also decreases rapidly - performance in cold weather is much more important - but it is still surprising and not a good sign. What is going on?

|

| Figure from [1] |

The article has an equivalent chart for ground source heating pumps (GSHP). At low temperatures, the GSHP efficiency remains high because the ground is still warm even though the air is cool. However in warmer weather the efficiency declines, much the same as with the ASHPs.

Possible reasons for the poor performance at high temperatures.

This analysis includes electricity consumption by the heat pump itself with its fan and pumps, plus the circulation pumps, any backup heaters and immersion heaters for the hot water cylinder. (This is the H4 system boundary). Immersion heaters are often used to top up the cylinder during sterilisation cycles, typically once a week or so, since this process needs temperatures above 60°C.

The article gives a number of possible reasons for the poor efficiency at high temperatures:

- Since there is less demand for room heating, the proportion of heat required for hot water is higher, and this is less efficient because the heat pump has to supply a higher temperature.

- The overheads for running circulation pumps, etc. are now a higher proportion of the electricity use

- Heat pumps are not optimised for warm weather demand.

- Lower room heating demand at higher temperatures means heat pumps are turning on and off frequently (cycling). There are several reasons why this makes the heat pumps inefficient, especially with run times of 6 minutes or less [2]

However, I would not expect such a sharp peak from these reasons, except possibly the last. Also, since the decline in efficiency continues into very warm weather, this suggests hot water has quite a lot to do with it. Another report on the same data [4] shows increasing COPs for hot water in the summer months, when just the heat pump is taken into account, ignoring immersion heaters and boosters. That suggests that immersion heaters are an important factor. Most of the heat pumps used a combination of heat pump and immersion heater for the hot water. In some cases the immersion heater alone was used in summer - so that the heat pump could be turned off. This could be the reason for the continued decline in efficiency in warmer weather - as the weather becomes warmer more households turn off the heat pump.

Using an immersion heater for hot water brings down overall efficiency very quickly. Assuming this is 100% efficient, your heat pump COP is 3.2, and a quarter of your heating is for hot water, the overall COP becomes 2.1. In the winter more of the heating is for hot water and so the effect is smaller.

Why would households turn off their heat pump in summer? That is a good question. I do not know the answer. Please tell me what you think.

Also, the overall COPs achieve are lower than I would expect. This will be partly due to using the immersion heater but I suspect that cycling is also a significant factor. The heat pumps installed 10 years ago were notoriously poor at turning down heat demand without cycling (modulation). In addition, heating engineers have a tendency to err on the safe side by over-sizing, on the possibly dubious grounds that lower efficiency is better than not enough heat.

Good heat pumps have peak efficiency at higher temperature, probably due to more accurate sizing.

Some installations are a lot better than others and the same article also looks at ‘good’ heat pumps and ‘very good’ heat pumps separated from the others by COP. This chart shows the results for these groups, albeit just the ‘broken stick regression’ lines (shown in red in the chart above).

|

| Mean ASHP performance using broken stick regression data from [1] Overall mean COP for each group is 2.3 (all), 2.8 (good), 3.3(v. good) |

The best heat pumps have higher efficiency and also start losing efficiency at warmer temperatures than the others, though not much. That suggests to me that the better performance is largely due to better sizing, so that the heat pump cycling problems start at a higher temperature.

My heat pump shows no decrease in COP – but does not provide hot water.

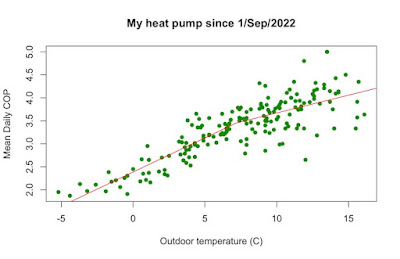

For comparison, here is a chart of similar daily average COP from my heat pump over the last winter season.

|

| Mean daily COP by mean daily temperature, with broken stick regression in red, for my heat pump using data from this winter. Overall COP is 2.9 |

You can see that my COP becomes more variable above about 7°C but overall efficiency continues to increase. It does not look very much like even the best performing cases from the 2012 installs. My heat pump, as is common these days, is inverter driven and very good at modulation, so even though it is oversized it can cope pretty well with low heat demand.

My heat pump is only supplying room heating, not hot water. However, it is unlikely that hot water is entirely to blame.

Modelled heat pumps show COP increasing again once room heating is no longer needed.

As the weather gets warmer there comes a point when all the heating is for hot water and the COP should level off or increase again. This is what I see with modelling, as in the chart below. These models do not include the cycling effect.

Variation in mean COP in warmer weather is due to using daily averages.

All the charts show increasing variation in COP at higher temperatures, as heat demand decreases. This is due to the use of daily average temperatures: some days can have a high mean temperature but still be cold some of the time. Demand for heating hot water tends to be at a particular time of the day, often early morning, and it is the temperature at that time that counts. Also if there is room heating demand, it will usually be at the coldest time. If you have heat pump monitoring and weather data at hourly time intervals or less, you should not see this variation.

Conclusions.

Try to use your heat pump as much as possible for hot water provision. Using the immersion heater is much less efficient.

Do not be too surprised if you notice a gradual decrease in efficiency in your heat pump in the warmer seasons. This is due to an increasing proportion of your heating demand being for hot water, which requires a higher temperature and your heat pump is less efficient in providing it.

However, if the downward trend is rapid that could mean problems with cycling i.e. turning on and off again frequently. In that case your heat pump is probably oversized and/or does not modulate very well. Modern inverter driven heat pumps are much more tolerant of oversizing as they are good at modulating.

If you have TRVs turned down on many of your radiators that could make your heat pump cycle on and off in warm weather. When the radiator valves shut off the effect is to reduce the volume of fluid in the radiator circuit, which means it cannot accept a lot of heat. In that case you could improve efficiency by turning up the TRVs although this would deliver heat where you do not need it.

If you are cycling even in cold weather, then your heat pump is too big. A buffer tank might help – or possibly not as it can introduce inefficiency too [3].

If you are getting a new heat pump, do choose one that it is inverter driven so less likely to cycle when heat demand is low. It also helps to get one the right size (see How big should your heat pump be?).

[1] Predicting future GB heat pump electricity demand (S.D. Watson, J. Crawley, K.J. Lomas and R.A.Buswell, in Energy And Buildings) (2023)

[2] The Effects of Cycling on Heat Pump Performance (EA technology) 2012

[3] How to correctly install heat pumps so that they work properly and efficiently (Renewable Heating Hub) Jan 2023

[4] Investigating variations in performance of heat pumps installed via the renewable heat premium payment (RHPP) scheme. (UCL Energy Institute) 2017

Some of the curves I've seen for scroll compressors show they are less efficient at the slower speeds I would expect when warmer outside

ReplyDeleteYou may not even need to run a legionella cycle, unless you have low turnover of water in your hot cylinder - so need to use the immersion heater. There is a very good guide to hot water temperatures and legionella in this Heat Geek video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oJeyc_cGIMU

ReplyDeleteGood post. One possible explanation for households turning off HPs in summer is that they have windows open for longer, and spend more time outside/in their gardens. This means HP noise can be more irritating - especially if the hot water cycle runs at night, with noise entering windows while householders try to sleep.

ReplyDeleteI'm a little surprised that UCL's broken-stick regressions show so little difference in peak-efficiency temperature. By eye, only about 1C between good and very good, and only about 0.5C between good and 'other' (poor, presumably).

It sounds to me that, for people using a HP for domestic hot water, there is a clear case for recommending running the hot-water cycle mid-afternoon/warmest part of the day (not mornings) to improve the COP.